2000 words | 5 minutes

Introduction

As digital technology has become more and more advanced, what virtual programs can provide to the mass market of consumers has been greatly enhanced. Video games, a form of entertaining computer program that was in constant expansion of both scale and variety over the past decades, have also become more capable of initiating a hybrid, interactive experience. This hybrid experience video games bring to the player can sometimes be so delicate, that it’s considered art by many people around the world. Being both an art student and a game designer, the researcher is always interested in investigating such a polarizing topic. However, in this essay, the focus is not on the artistic value of video games — which has been done by many others long before. Instead, the researcher will analyze the art of systems in video games. After field researching various genres of video games, the researcher aims to prove that interactivity in video games can be artistic, and can differentiate video games from any other forms of art. This essay’s main focus will be on making connections between video games, responsive systems, interactivity, and art.

Video games and art

To get through the connections between the four factors addressed above, I will first analyze the relationship between video games and traditional art forms. Despite being a well-discussed topic, it is still worth mentioning because it’s an essential part of my thesis statement.

Just like how literature, music photography, and theater art are integrated into the art of filmmaking, video games can contain many different art forms. Thanks to the flexibility of digital media, almost every art form in existence can be merged into a video game. Universally speaking, most video games employ the same principles as traditional canvas arts: perspective, form, value, and more, to create a window into an imaginative world[1]. Depending on the media and genre, a video game can be composed with multiple forms of art, including the ones that are thought to only exist in real life. For example, in the platformer game Limbo, the story is delivered without the characters saying a line[2]. Although animated digitally, the scenes and gestures truly show the artists’ mastery of theater arts.

Only combining several other art forms can certainly make a computer program artistic, but is not enough to make a new type of art. Take film making as an example again — movies were once considered a “series of photography” in its early stage[3], but later became an important art medium thanks to the technique of montage. Digital media, while able to joining all traditional art forms together, needs a unique core technique enough to define itself as an independent form of art. This means that the technique should be capable to give a non-art digital program artistic value without relying heavily on certain other art styles. From my understanding of game design and art, this core element is the design of interactive systems.

Video games and interactivity

Until this day, people still haven’t come to an agreement on what the first video game is. There are several candidates, including Tennis for Two[4], OXO[5], and Spacewar![6]. However, these programs all share a similarity: they are all interactive. At least one method of input is required to exist in the program since the very start of video game history. Unlike radios and TVs, instead of using the input to switch between multiple streams of content, video games respond to an input by directly changing the content itself, no matter if the change is displayed, broadcasted, or stored in the database. It was this kind of immediate and preservable feedback that made video games “interactive”. However, to make an interactive computer program into a video game, a designer also has to meet the other fundamental factors of game design: Goals, rules, problem-solving, entertainment, etc.[7] Just like a board game needs its rules to be executed when being played, a video game also needs the program to gather all the inputs and logically organize them to be playable. Therefore, in a video game, there are not only singular immediate interactions but also complex, systemic interactivity.

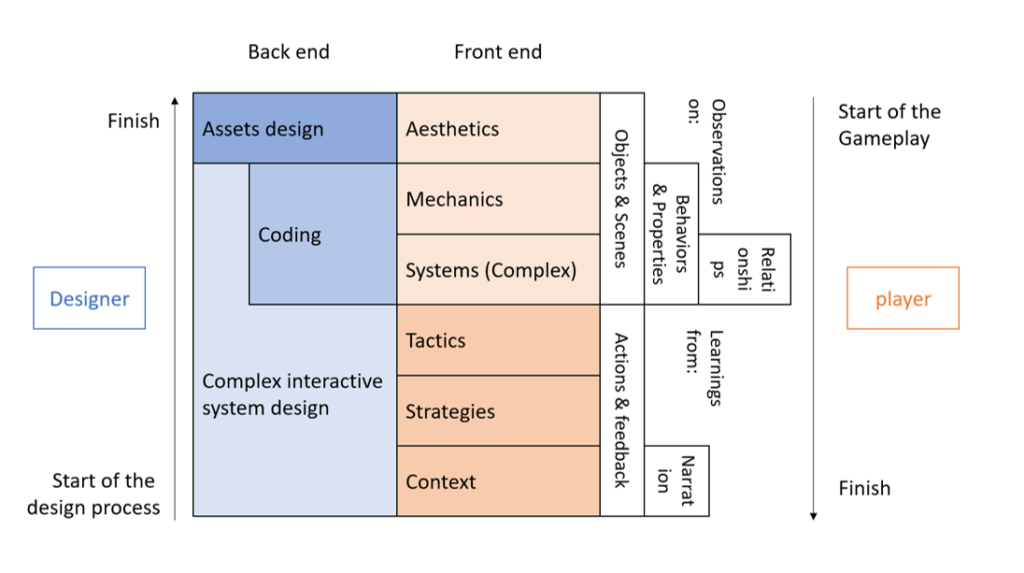

But what is complex and systemic interactivity? Complex systems are systems that do more than the sum of each part of them, and they are everywhere in our daily lives[8]. In fact, we rely on complex systems to live. We live under the laws of physics, the earth’s ecosystem, our nation’s constitution, and many more systems that give feedback to our actions. Our living quality is optimized by complex systems too, such as vehicles, artificial chemicals, electronics, and the main topic of this paper — video games. Viewing from the most fundamental aspect, most complex systems in a video game can be explained with programming languages and electronic routings, but they don’t represent systemic interactivity. The ones on the user’s end do, such as inventory, messaging, and battling. These systems are closer to people’s common sense, hence are easier to interact with. All of these systems are composed of individual objects’ properties and behaviors, as well as their relationships with other objects in the scene.[9] By observing these patterns, the player gets to understand the complex systems under the game’s surface, and ultimately develop their own tactics and strategies of playing.[10] Along the way, the player will also get familiar with the aesthetics and the narrations of the game.

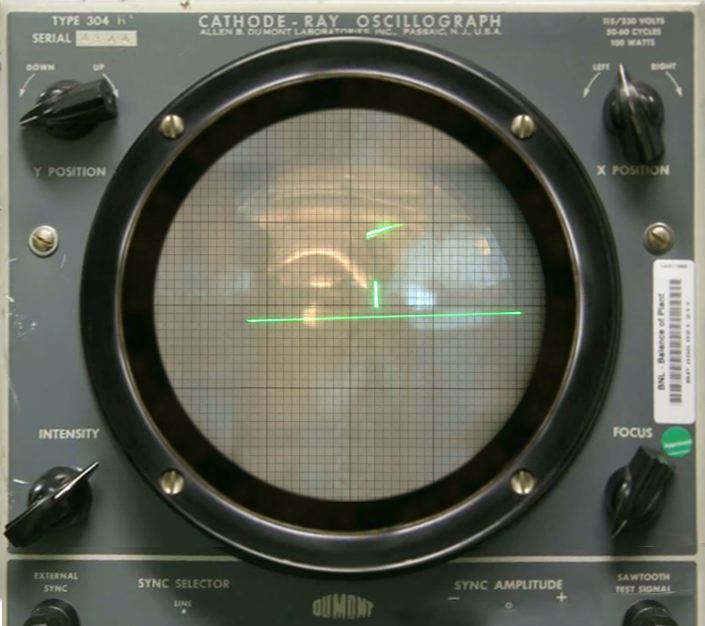

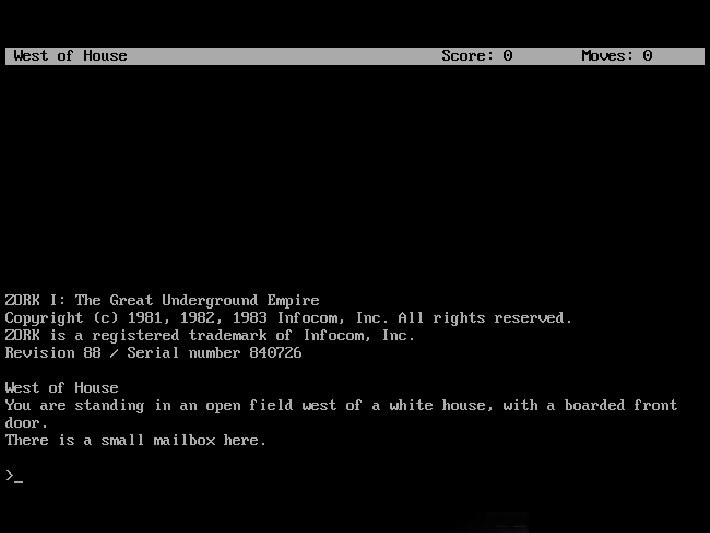

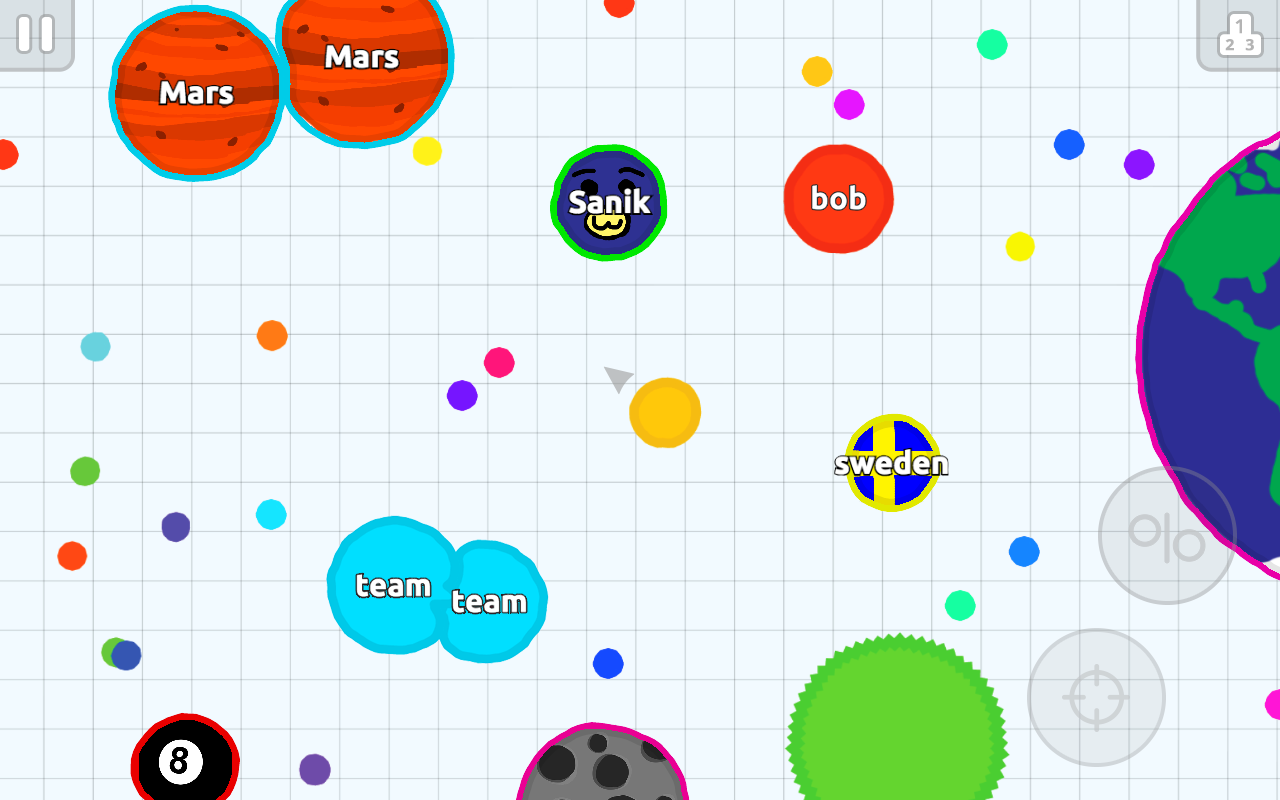

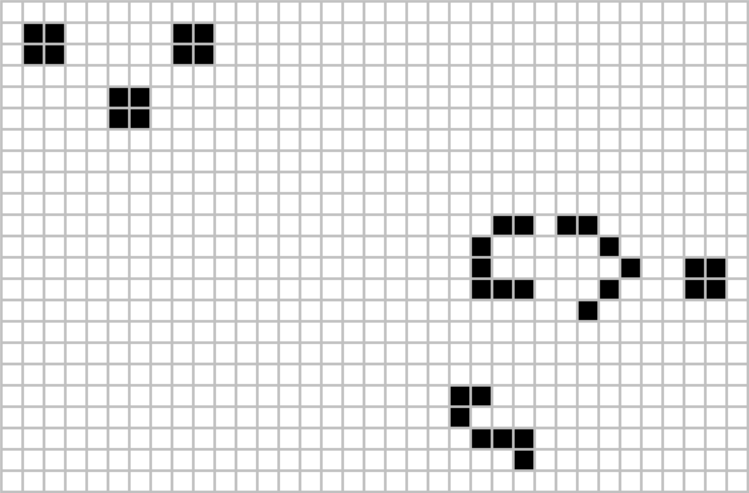

However, these two elements are not as essential to a video game as interactivity. Input and output are an inseparable part of video games, while there are plenty of games out there that has other parts of them taken away. MUD games such as Zork[11] does not have any asset besides their logo, and vector multiplayer games such as Agar.io[12] contains minimal assets and no narration at all. A pioneer arcade game located in Brooklyn, New York called Line wobbler uses an LED strip as its only monitor. Thanks to the interactive system composed of gestures, abilities, and well-managed difficulty curves, the game successfully create a mind-blowing experience without even having more than one line of pixels in front of the player’s eyes[13]. On the other hand, even a “zero player” video game like Conway’s Game of Life requires a temporary player to put in the blocks before the game starts, and eventually, the game will also generate a result as feedback to the player that has already quitted controlling[14].

In a normal game design process, the systems are always the ones that get sketched out first.[15] What is this fantasy world composed of? How will the player interact with this world? What emotions will the player experience from these systems? Questions like these are the prerequisite of the programming and assets-making section. However, from the player’s end, the assets are the ones that get exposed and remembered first. The player needs continuous actions and feedback to finally figure out the systems behind the materials, and finally the motives of the designers behind the scene.

To sum up, complex, systemic interactivity are always the most fundamental and inseparable part of a video game. A video game may not contain assets or a storyline, but requires a system of interactions to exist.

Interactivity in video games and art

After analyzing the relationship between video games, art, and interactivity, we can finally come to the most controversial part of my argument: Interactivity in video games is artistic and is capable of making video games a unique form of art.

Interactivity is a property that almost doesn’t exist in all the eight traditional art forms. Although fine arts and performance arts that change by the audience’s actions exists, those changes are not enough to form an interactive system. The interactive drama Sleep No More allows the viewers to walk around the stage to observe the story from different perspectives, but the content in the storyline doesn’t respond to the player’s actions[16]; The Concave Convex Mirror sculpture by Anish Kapoor shows the reflection of the viewers, yet this feedback is linear, predictable and singular.[17] In all traditional forms of art, the viewer is the receiver, the observer, the bystander. They can only passively accept what’s already determined by the artist, with little to no means to change the work of art. However, systemic interactivity, being a property and essential to video games exclusively, has the power of enhancing other forms of art as well as creating an entirely different artistic experience.

The existence of actions and feedback can be used to magnify the power of a traditional art form in a video game or distort the original meaning it brings. Here are a few examples of these enhancements.

- Making realistic visual art more lively: In the role-playing game Red Dead Redemption 2, all models of wild animals are animated and moderated responsively to the environment.[18] As an extreme example, if a player rides a male horse through a snowy mountain, it will show various reactions such as exhaustion, freeze, hunger, etc. through its body gestures. Even its testicles will shrink because of the cold weather.[19] Animating a realistic 3D sculpture interactively can dramatically increase the sense of immersion of the player.

- Composing music adaptively to the player’s pace: In the horror platformer game Little Nightmares[20], the background music changes smoothly based on how dangerous the situation is to the player. When listening as a whole, every player’s playthrough creates an hour-long symphony of their own pace. A skilled player can have the music changing swiftly and rather peacefully, while some players may create a long-lasting horror music piece.

- Tell the story as the player pass through challenges: In the role-play game To The Moon, the player needs to solve technical issues to trace back an old man’s memory[21]. The storyline gets revealed backward only when the player continues to solve problems. After multiple plot reverses, the player finally sees the tear-drawing story of the dying man’s life. The narration is pre-written, but since every part of it is revealed as a reward to the player’s “hardworking”, it gives the player a sense that they discovered the story themselves out of nowhere.

Not only can interactivity perfect the original arts in a game, but it also appeals to emotion and deliver concepts just like other forms of art do, but in a different way. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, art is defined as “The expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”[22] Here are four examples of interactions that can be defined as art.

- Making the storyline customizable by player’s decisions: In role-playing game Cyberpunk 2077 (and many other open-world games), the player has an enormous amount of choices when it comes to “what to do”[23]. Every major action, including talking, buying, killing, etc. will more or less affect the status of the player. The player can also choose to get into a relationship with other NPC characters freely, and vital decisions like this may affect the ending of the storyline. By allowing the players to write their own plot, they will no longer feel like an observer of the story, but instead a character inside this world.

- Let the player face moral ambiguity: In strategy game Papers Please, the player acts as a border-crossing immigration officer of a dystopian country and has to decline everyone that fails to meet the requirements[24]. Throughout the gameplay, many people will come to the player telling their struggles to beg for acceptance. However, by falsely letting the immigrant in, the character will lose wages that are used to buy medicine and food for his family. By putting heavy responsibility and guilt on the player’s shoulder through decision-making challenges, the overwhelming desperation of a dystopian country gets fully rendered.

- Creating emotional moments from human interactions: In the online role-play game Journey, the player plays as a lonely traveler in the desert, exploring the ruins of an ancient civilization[25]. The system will randomly pair two players up when they enter the game and have them encounter each other at some point. These two players will then be each other’s only companions throughout the journey. However, there’s absolutely no way to talk to each other or to add each other as friends. Therefore when the journey ends, the only friend of the player will also fade out of this world. Trying to say farewell to each other with gestures and dancing can trigger the purest emotions from the bottom of one’s heart. What’s unique to the player is not only the playing memory but also the irreplaceable travel buddy.

- Encouraging the player to build narrations, characters, and environments from scratch: In the online sandbox game Minecraft, one of the best-selling video games of all time, the player enters the world with absolutely no instructions, no context, no connections, and no property[26]. It all relies on the player itself to figure out how to build, farm, craft, mine, and fight. There is no goal instructed in the game, so many choose to build more and more structures and farm more and more animals. The game also features a “red stone” mechanic, allowing the player to make a simple circuit, but once the circuit is large enough it’s even capable of making a mini-computer inside the game from scratch. After years of hardworking, the players will look back and recall the countless amount of stories created by themselves by simply walking through the giant world built brick by brick. After the multiplayer feature becomes popular, the player can also recall precious memories with old-time friends. Friendship may not last forever, but what they built together in Minecraft stays the same. Released in 2011, Minecraft packs decade-long, completely personalized visual art projects, storytelling, and emotions and gives it all back to the player whenever they run the game again. Achieving all of these with no narration and only several simple mechanics shows the huge artistic potential of interactive systems in video games.

All of these examples above show how interactivity can be the reason why video games are a form of art. But besides first-handed analysis, there are also professional voices in the field of art that values systemic interactivity. MoMA celebrated video games as an artistic medium in 2012 by exhibiting 14 video games based on not only their visual quality but also “the elegance of the code and the design of the player’s behavior”[27]. Pong, being the first commercial video game[28], has almost no visual, sound nor narrative complexity, yet still gets selected because of its contribution in reshaping people’s interaction with their monitors and images in motion. This exhibition of MoMA is the proof that more and more experts are embracing the art of player-machine interactions in video games.

Summary

From October 1958 to May 2021, from one of the earliest video games Tennis for Two to the latest triple-A game It Takes Two, no matter how different the changes are of video games, there are always two things that remain the same: The player controls the game; the game responds to the player. With systems that respond and alter based on people’s decision-making, video games can deliver exclusive concepts and emotions that nothing else can express. After seeing how much artistic value can interactivity in video games bring to us, we can come to an undeniable conclusion: Interactivity in video games can be artistic and can differentiate video games from any other forms of art.

Bibliography

Solarski, Chris, and Tristan Donovan. Drawing Basics and Video Game Art: Classic to Cutting-Edge Art Techniques for Winning Video Game Design. New York, NY: Watson-Gruptil, 2012. This book introduces how to make drawings that adapts to video games to traditional artists. It mentions the similarity between graphics in video games and scenery in traditional canvas arts.

“Playdead’s Limbo.” Playdead. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://www.playdead.com/games/limbo/. The official website of Limbo, including screenshots and trailer that shows its excellency in staging and theater art.

Cook, David A. “History of Film.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., February 16, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/art/history-of-the-motion-picture. A brief history of films and film-making as an medium of art. It introduces the early stage of films.

“The First Video Game?” BNL, October 21, 2008. https://www.bnl.gov/about/history/firstvideo.php. An introduction of Tennis for Two, along with coverage of other stories about the game’s creation. It argues that Tennis for Two is the first video game.

Donovan, Tristan. “Pp. 1-9.” Essay. In Replay: the History of Video Games. Lewes: Yellow Ant, 2010. A detailed history of video games, containing OXO as potentially the first video game.

Goodavage, Joseph F. “Space War!: A Computer Game Today, a Reality Tomorrow?” Saga 44, no. 8 (November 1972): 34–94. This article talked about Spacewar!, one of the first video games from the perspective of the 1970s. It introduces Spacewar! as the romance dawn of a new digital and space exploration era.

Prensky, Marc. “Chapter 5.” Essay. In Digital Game-Based Learning. Paragon House, 2007. This is an educational book about designing digital-based games. It mentions ten fundamental factors that makes a video game.

Chaplin, Heather. “The Ludic Century: Exploring The Manifesto.” Kotaku, December 9, 2013. https://kotaku.com/manifesto-the-21st-century-will-be-defined-by-games-1275355204. This is one of the two articles on the webpage, taking about how video games are the future of the 21st Century. It mentions the definition and application of a complex system.

Nacke, Lennart. “Game Systems and System Dynamics.” The Acagamic, March 29, 2021. https://acagamic.com/courses/intro-to-game-design/game-system-dynamics/. The article introduced systems in a video game layer by layer. It talked about how object and their behaviors forms systems in a video game at the beginning.

Sankalia, Jainan. “Layers of Player Understanding.” Gamasutra, July 5, 2013. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/195320/layers_of_player_understanding.php. This is an online article about how player understands a video game by time. It points out the Aesthetic-Context sequence in a graph.

Loguidice, Bill, and Matt Barton. “Zork (1980).” Vintage Games, 2009, 371–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-240-81146-8.00035-x. This is an article about Zork, a 1980 MUD game. It explains how the game works with only text and nothing else.

Takahashi, Dean. “The Surprising Momentum behind Games like Agar.io.” VentureBeat. VentureBeat, February 12, 2017. https://venturebeat.com/2017/02/11/the-surprising-momentum-behind-io-games-like-agar-io/. This article talks about Agar.io and simple games similar to it, and how they win in the casual gaming market.

Robin B. “Line Wobbler.” itch.io, December 4, 2014. https://robinb.itch.io/line-wobbler. This is the official page of Line wobbler, with a video demonstrating how it works with only a strip of LEDs.

Conway, John. John Conway’s Game of Life. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://playgameoflife.com/. This is the official website of John Conway’s Game of Life, including explanation of the rules and a ready-to-play embed of the game. It explains how it does not need a player during the game, but needs one before the game starts.

Schell, Jesse. The Art of Game Design: a Book of Lenses. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2020. This book explains the fundamental principles and detailed methods of game design. It mentions that developing concepts and systems are the first steps of making a game.

“Sleep No More.” McKittrick Hotel. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://mckittrickhotel.com/sleep-no-more/. This is the official website of Sleep No More, with detailed description as well as pictures of the show.

Kapoor, Anish. “Concave Convex Mirror (Diamond).” Anish Kapoor. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://anishkapoor.com/6698/concave-convex-mirror-diamond. This is the official showcase webpage of Anish Kapoor’s Diamond Concave Convex Mirror sculpture.

Reilly, Luke. “Red Dead Redemption 2 Review.” IGN, October 25, 2018. https://www.ign.com/articles/2018/10/25/red-dead-redemption-2-review. This is the official review of Red Dead Redemption 2 from IGN. It describes how detailed the game’s visuals and animations are, and how the game interacts with the play tester.

Morrison, Matt. “Red Dead Redemption 2 Is So Realistic That Horses’ Balls Shrink In Cold Weather.” ScreenRant, September 22, 2018. https://screenrant.com/red-dead-redemption-2-horse-balls-shrink/. This is a review article that focuses on one detail in the game Red Dead Redemption 2: The testicles of male horses shrinks in cold weather.

Skrebels, Joe. “Little Nightmares Review.” IGN Southeast Asia, April 26, 2017. https://sea.ign.com/little-nightmares/114892/review/little-nightmares-review. This is an official review of Little Nightmares from an IGN play tester. It describes the artistic value of the game.

Gallegos, Anthony. “To the Moon Review.” IGN, January 18, 2012. https://www.ign.com/articles/2011/11/30/to-the-moon-review. The official review of the game To The Moon from IGN. It describes how the game shows the old man’s life story as the player progresses to solve problems.

“” In Lexico. Lexico, n.d. https://www.lexico.com/definition/art. The definition of art on Lexico.com, using Oxford’s dictionary’s database.

Marks, Tom. “Cyberpunk 2077 PC Review.” IGN, December 8, 2020. https://www.ign.com/articles/cyberpunk-2077-review. This is the offical review of Cyberpunk 2077 from IGN. It briefly describes how the open world game gives the player freedom to make up the story, as well as how the game employs different endings.

Cobbett, Richard. “Papers, Please Review.” IGN, August 13, 2013. https://www.ign.com/articles/2013/08/12/papers-please-review. This is the official review of Papers, Please from IGN. It mentions how the game uses moral ambiguity as tools to pressure the player.

Clements, Ryan. “Journey Review.” IGN, September 2, 2016. https://www.ign.com/articles/2012/03/01/journey-review. This is the official review of the game Journey from IGN. It introduced the game’s unique mechanics and special way of interactions.

Gallegos, Anthony. “Minecraft Review.” IGN, June 29, 2016. https://www.ign.com/articles/2011/11/24/minecraft-review. This is the official review of Minecraft from IGN. It describes the game’s lack of essential elements in many other video games, such as narration, goals and tutorial.

Solon, Olivia. “MoMA to Exhibit Videogames, From Pong to Minecraft.” Wired. Conde Nast, December 22, 2017. https://www.wired.com/2012/11/moma-videogames/. A coverage of MoMA’s 2012 video games exhibition. It reports the rules of selection of the exhibition.

Sellers, John. “Pong.” Arcade Fever: The Fan’s Guide to The Golden Age of Video Games, August 2001, 16–17. This is a magazine article introducing Png to the arcade lovers. It talks about Pong being the first commercial video game, and its impact on video games history.